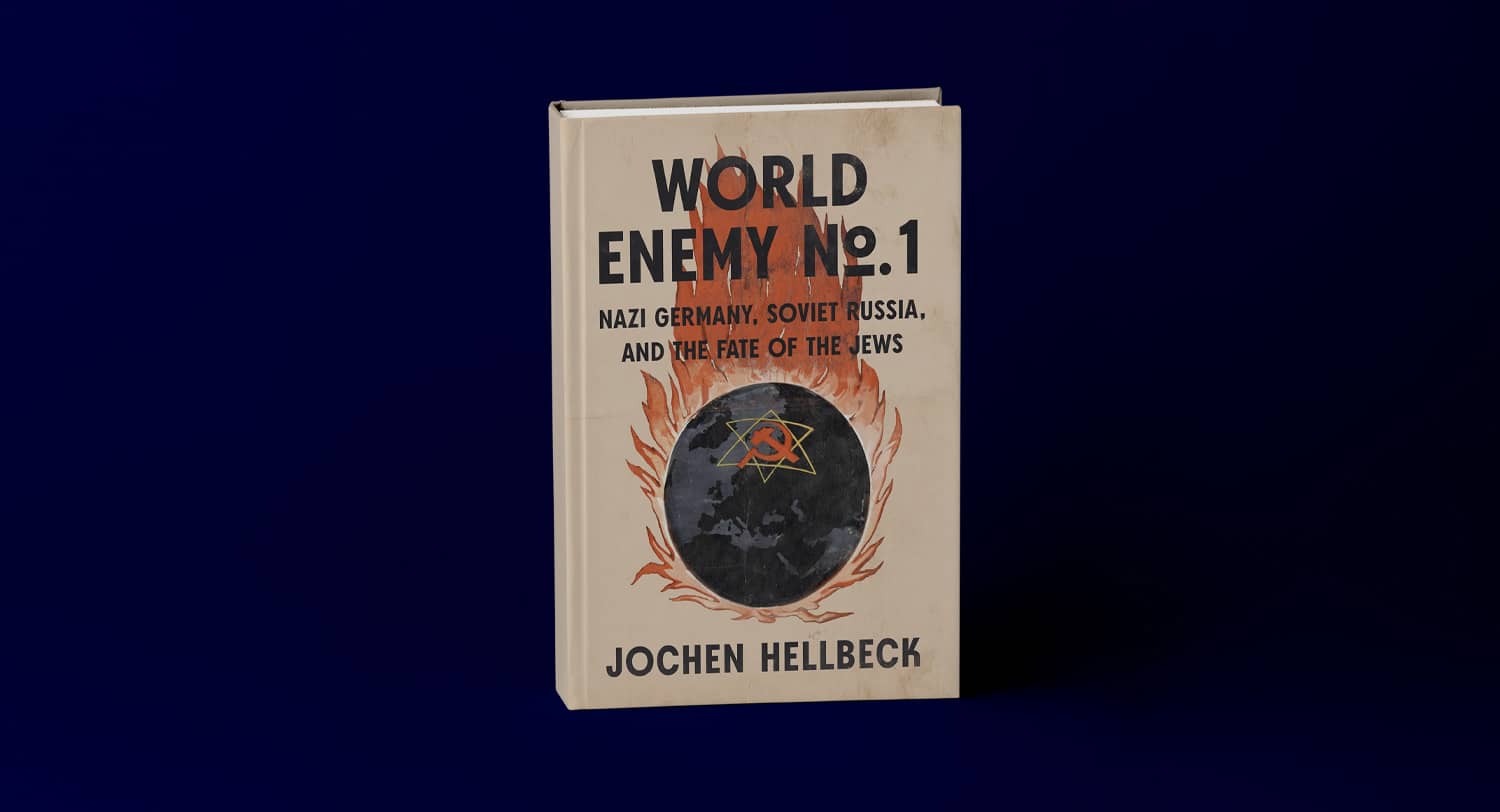

Jochen Hellbeck, World Enemy No. 1: Nazi Germany, Soviet Russia, and the Fate of the Jews, Penguin Press, 2025

Legend has it that when the first chancellor of West Germany, Konrad Adenauer, crossed the Elbe River by train, he lowered the shades and remarked, “Here we go, Asia again.”

As a Rhinelander, Adenauer, who had served as mayor of Cologne during the Weimar Republic, was intent on Westbindung, binding Germany to the West. After North Korea invaded South Korea in June 1950, Germany was welcomed into the western club. In 1954, during a speech to the German Press Club in Bonn, former president Herbert Hoover (who, incidentally, had met with Hitler in the Reich Chancellery in March 1938 and praised the prospect of Nazi rule in Central and Eastern Europe as a force for stability) even declared that a revived German nationalism would be a good thing. “The German people,” Hoover said, “have before now been the bastion of Western civilization which deterred its destruction by Asiatic hordes.”

In his well-researched and provocative new book, World Enemy No. 1: Nazi Germany, Soviet Russia, and the Fate of the Jews, Jochen Hellbeck carefully examines Germany’s greatest clash with Soviet Russia–Operation Barbarossa, the extraordinarily brutal invasion that Hitler launched in June 1941 and that became his downfall. Hellbeck is a German-born historian who teaches at Rutgers University and who has written extensively on the Soviet Union. He now draws on numerous testimonies, letters and diaries from Soviet and German archives and sources to depict the sanguinary struggle on the eastern front. While earlier works such as Lucy Dawidowicz’s The War Against the Jews have focused on the origins of German anti-Semitism and Hitler’s implacable hatred of European Jewry, Hellbeck adopts a different approach. Arguing that the Soviet lands were ground zero for the Holocaust, Hellbeck maintains that Hitler’s main obsession was “Judeo-Bolshevism,” which he saw as a dire threat to the German Reich.

In Hellbeck’s view, the Nazis viewed the Kremlin as the most powerful and diabolical Jewish organization in the world: ”World Enemy No. 1” in their words. “As Hitler noted with concern in 1936, the rulers in Moscow propagated the `most extreme’ variant of the modern Enlightenment faith, which had first provoked the French revolution and was now sending the world hurtling toward a global showdown,” Hellbeck writes. “Coded by the Nazis as Jewish, the Communist creed of universalism and interracial solidarity stood in the way of Hitler’s plans to fulfill the German people’s historical destiny as the world’s master race.” Nazi propagandists staged a touring exhibition in 1936 called “World Enemy No. 1—Bolshevism” that depicted Jews with misshapen bodies and portraits of Bolshevik leaders as thieves.

Hellbeck asserts that the West has failed to acknowledge sufficiently not only the central role that the Soviet Union played in Nazi demonology, but also the leading part that the Red Army played in defeating the Third Reich. By 1942, two million Soviet POWs had died in German captivity of undernourishment, exposure and disease.

Hellbeck also devotes much attention to the killing sprees that the German Army and SS went on in the eastern territories, which prompted partisan resistance. After the German 6th Army surrendered at Stalingrad in January 1943, Hitler warned Germans what awaited them if they faltered in their struggle, describing Bolshevism as tantamount to “burned cities…destroyed cultural monuments…brutally slaughtered masses of people, victims of the hordes from inner Asia, just as in the time of the Hun and Mongol invasions.” The longer the war went on, the more radical the Nazi leadership became. According to Hellbeck, “By 1943, Nazi leaders were no longer content to eliminate all Soviet Jews, and in their wake, all Jews of Europe. Their vision of the tempering of the Germanic race foresaw the slaughtering of `Russian-Asiatic’ soldiers and civilians for centuries to come.”

Hellbeck notes that the Soviet authorities did not single out Jewish suffering during or after World War II. Instead, it became subsumed under the broad rubric of “anti-fascism.” This was in part an outgrowth of Russia’s own tenebrous history of antisemitism. At the same time, East Germany also sought to exempt itself from any responsibility for the crimes of Nazism by claiming that the communist movement had incarnated anti-fascism all along. It was a victim of Nazism that need not show repentance for Hitler’s crimes.

What are we to make of Hellbeck’s sweeping work? His emphasis on Hitler’s fixation with “Judeo-Bolshevism” is diametrically opposed to the recent writings of the Irish historian Brendan Simms, who argued in his revisionist history Hitler: A Global Biography that Hitler actually believed that the West, not the East, formed the cardinal threat to Germany.

Simms criticized Hellbeck for minimizing Hitler’s animus towards international capitalists as the true German foe.

For all the bluster about Bolshevism, the irony is that it was the Germans, more than any other foreign power, who were culpable for the rise of Soviet rule. It was German military leaders who arranged in the spring of 1917, at a moment of revolutionary tumult and fervor in Russia, for the return of Lenin from exile in Zurich in a sealed boxcar. Germany then signed the punitive, if short-lived, Brest-Litovsk treaty in 1918 with the Bolsheviks. During the Weimar Republic, Germany and Russia agreed to the 1922 Rapallo Pact, which helped ensure cooperation between Berlin and Moscow, allowing the Reichswehr to subvert the provisions of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. Nor was this all. It was none other than Hitler and Stalin who agreed to the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, which contained secret annexes carving up Poland and the Baltic States. Hitler was perfectly capable of subordinating his hatred of Bolshevism to geopolitical dictates.

Hellbeck is right to stress the Soviet Union’s indispensable part in defeating the Third Reich, but he may at times elide the similarities between the two. Nor does he mention the steady stream of pro-Soviet propaganda disseminated by the Roosevelt administration during the Second World War, when Uncle Joe was depicted as an amiable fellow who was fighting for the same principles as the Western allies. The one wartime leader who had no illusions about the Soviet Union was Winston Churchill. “If Hitler invaded hell,” he remarked shortly after Operation Barbarossa began, “I would at least make a favorable reference to the devil in the House of Commons.” That is essentially what he did in allying Great Britain with the Soviet Union.

Ultimately, Hellbeck seeks to refocus the Germans’ hatred away from the Jews and center it more generally on Soviet communism. This effort is reminiscent of the Yale historian Timothy Snyder’s widely praised book Bloodlands, which stresses the locus of German (and Russian) bloodletting – all of Eastern Europe. Hellbeck draws a distinction between Europe’s Jews, who were exiled and persecuted, and Soviet Jews, who were murdered immediately. But the wartime conditions in the East provided the cover for the mass murder that Hitler wished to perpetrate. Anyway, was “Judeo-Bolshevism” the necessary precondition for Hitler’s plans to exterminate Jews, whenever and wherever he could?

The Germans harbored many hatreds and targeted communists. But as the political philosopher Leo Strauss observed, “The Nazi regime was the only one of which I know which was based on no principle other than the negation of Jews.” The Nazis murdered the largest number of Jews in capitalist Poland, not Soviet Russia. The results of this genocide – specifically and proudly cited in Hitler’s last will and testament – speak to an all-consuming and very specific enmity, which cannot and should not be avoided.