On September 24, Syrian President Ahmad al-Shara’a addressed the UN General Assembly in New York, where he is still on the UN sanctions list for his leadership of an al-Qa’ida affiliate (though he is likely to be de-listed soon). The transformation of al-Shara’a from wanted terrorist into respected statesman has taken place with remarkable speed. Few would have expected a man who celebrated the events of October 7 to enter into negotiations with Israel on a bilateral security agreement.

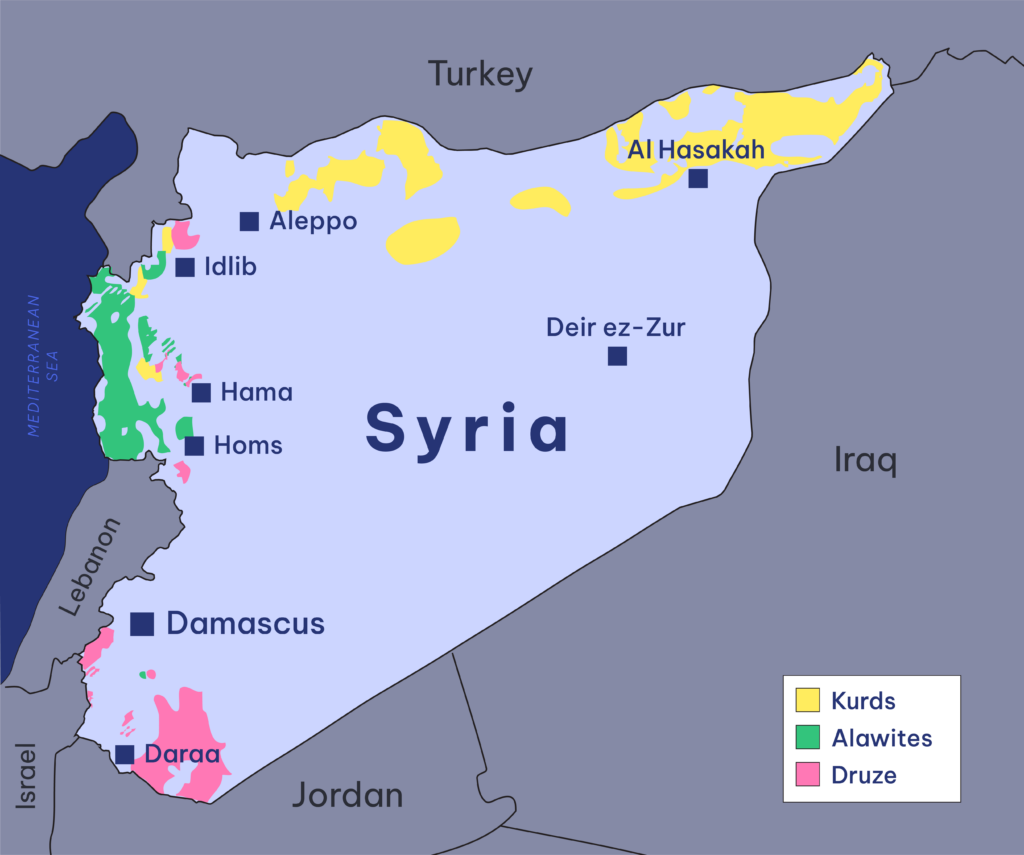

Yet amidst the fanfare surrounding al-Shara’a, two massacres of Syrian minorities have taken place on his watch: the Alawites in March and the Druze in July.

Under Asad, the Syrian regime would never have admitted that its troops or associated militia forces committed atrocities. So the candor of the new government is a step forward. Yet al-Shara’a faces a dilemma in following through on his promise to hold perpetrators of the massacres accountable.

The Alawite Massacre

Asad and his extended family are Alawites. Both Bashar and his father Hafez drew heavily on their community to man top positions in the military and security services, creating deep resentment toward the Alawites. On March 6, fighters still loyal to Asad launched an uprising against the Shara’a government, reportedly killing 200 troops.

This became the pretext for revenge. For three days, government forces and allied militias went door to door in Alawite towns, murdering and humiliating their residents. The killers sliced out one young man’s heart and placed it on his body. A UN report on the violence, released in August, put the death toll at 1,400 and confirmed that the perpetrators targeted Alawites simply based on identity, not any alleged connection to the Asad regime.

On July 13, the investigative committee on the Alawite massacre presented President al-Shara’a with its conclusions. The government held a press conference on July 22 to disclose principal findings without publishing the report. The committee’s spokesperson, Yasser al-Farhan, and its head, Judge Juma’a al-Dubais al-Enezi, said they were able to determine the identities of 298 government-connected individuals involved in violations and had passed their names on to the Ministries of Justice and Interior. The committee also identified 265 perpetrators linked to pro-Asad militias. However, any prosecution lay outside the committee’s mandate, they said.

So far, the government has not announced any formal charges, indictments, or other legal proceedings in the March atrocities. The fact-finding committee indicated that 37 arrests had been made, and in some cases the government has released mugshots of those arrested along with names. But there is no clarity regarding what, if any, judicial process the government will follow to determine guilt or innocence.

The Druze Massacre

The violence against the Druze began on July 11 when a Druze merchant was ambushed by armed bedouin tribesmen on the highway between Damascus and Suwayda. Eight days of fighting broke out between Druze and bedouin, with government forces often taking the bedouin side rather than stopping the violence. Eventually, a US-backed ceasefire ended the clashes.

A Reuters investigation documented the execution of unarmed captives, some while on their knees. Its reporters verified a video showing the murder of a 60-year old Druze man after young gunmen demanded to know if he was Muslim or Druze. As evidence accumulated, it became clear that what had taken place was a slaughter of Druze civilians, not a clash between rival gangs. An initial UN inquiry reported 1,000 dead, including 539 Druze civilians, in one group of villages. Those deaths included 196 extrajudicial executions. Some accounts claimed as many 3,300 dead, albeit without documentation.

The Syrian Ministry of Defense acknowledged that men in military fatigues committed “shocking and gross violations.”

As he did in the case of the Alawites, al-Shara’a set up an investigative committee in July. Whereas the previous committee was independent, this one falls under the Ministry of Justice. The significance of the change remains uncertain. In any event, the Druze have not proven cooperative, preventing the government’s investigators from entering Suwayda on the grounds that their effort is “illegitimate.” Their preference is for an international investigative committee that would not be beholden to al-Shara’a.

The July massacres accelerated a shift in the Syrian Druze community. For over a decade, three sheikhs, each with his own following, led the community. Two sought a cooperative relationship with Damascus. The third, Hikmat al-Hijri, denounced al-Shara’a and his government as an “extremist group wanted by international justice.” He also welcomed Israeli intervention in the conflict, while the other two rejected it.

The July massacre strengthened al-Hijri’s position within the Druze community, sidelining his two rivals. Whereas al-Shara’a opposes federalism, al-Hijri has called for a decentralized state. Some Druze demanded outright independence as part of a demonstration in August in Suwayda.

Damascus turned to Washington to help address this challenge. With support from Jordan, which shares a border with Suwayda, the US and Syrian governments announced a plan to restore stability, although al-Hijri promptly rejected it. The plan approved the idea of having an international committee investigate the killings in July, but a Druze group objected to a clause that said perpetrators would be held accountable under Syrian law. In light of the Syrian failure to prosecute anyone for crimes against either Alawites or Druze, it is not hard to understand the objection.

What About the Kurdish Minority?

The greatest challenge to the ultimate unification of Syria is the relationship between Damascus and the Kurdish minority in the northeast. While the Druze have armed groups, the Kurds have spent over a decade building up their army, the largest element of the US-led coalition that fought the Islamic State inside Syria. The Kurds have also built a local administration that resembles the Kurdish autonomous region across the border in Iraq.

In a bid to prevent a showdown between Damascus and the Kurds, Washington brokered an agreement in March that nominally paved the way for the integration of Kurdish-led forces into the national army. Yet the March agreement only papered over the divide between the insistence of al-Shara’a on central control and the Kurdish demand for decentralization. As progress stalled, sporadic fighting ensued. The Alawite and Druze massacres likely reinforced the Kurdish suspicions that self-defense and autonomy are their safest option.

The Dilemma

If there is hope for reconciliation between al-Shara’a and his country’s minorities, it lies with Washington. President Trump has committed to lifting US sanctions on Syria but that has not yet been completed. And the White House has expressed hope that al-Shara’a would govern inclusively and treat minorities fairly. While no firm benchmarks have been set, judicial accountability for the perpetrators of massacres would surely be welcomed by both the US and by the Syrian minorities.

The dilemma for al-Shara’a is that imposing accountability for atrocities would require him to turn on some of his own comrades-in-arms. He came to power as an avowed Islamist and, while projecting an image of moderation abroad, he seems unready to challenge the extremists in his own ranks.

Yet if he cannot hold the killers accountable, al-Shara’a may find it increasingly difficult to recruit the level of international aid needed to keep his regime in power.