Wedged between Turkey and Iran, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq has become a crossroads of two competing regional orders.

As Iran’s axis of resistance frays under economic strain and regional backlash, Tehran is scrambling to reinforce its influence through coercive diplomacy and the creation of a new strategic corridor to the Mediterranean. At the same time, Turkey positions itself as an energy and transport hub, submitting a draft deal with Iraq to expand cooperation in oil, gas and power and signalling Ankara’s ambition to anchor Gulf-Mediterranean trade through northern Iraq.

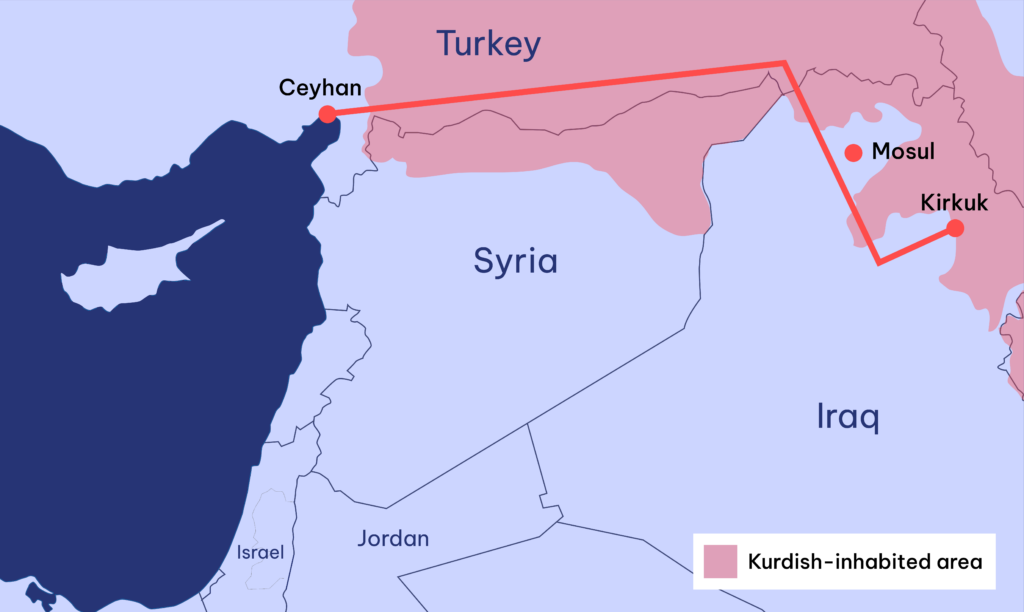

Turkey’s hold is transactional: Kurdistan’s oil is pumped to the Turkish Mediterranean port of Ceyhan, its trade must pass the Ibrahim Khalil border crossing, its water flows down the Tigris. Turkey leverages these chokeholds to shape Erbil’s decisions and secure Ankara’s regional reach. Meanwhile, Iran’s grip is coercive: it operates through armed groups, occasional missile strikes, gas dependence, and political clients in Baghdad.

Between these twin pressures, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq survives by trading degrees of autonomy for access, by remaining silent in return for stability.

The Kurds make up sizable minorities in four states. In Turkey, Kurds constitute roughly 18–20 percent of the population, about 15 million. In Iran, they are about 10 percent or roughly 8 million. In Iraq, Kurds make up around 15–20 percent, some 6–8 million, anchored in the Kurdistan Region of northern Iraq. In Syria, Kurds account for about 10 percent or 2.5 million.

The Kurdistan Region of Iraq is an official semi-autonomous region with its own government, parliament, and presidency, formally recognized by Iraq’s 2005 constitution as a federal entity. Beyond Iraq, a separate de facto autonomous Kurdish administration, Rojava, has emerged amid Syria’s civil war.

Turkey’s Economic Leverage

One of the centerpieces of Turkish leverage over Kurdistan is the Kirkuk–Ceyhan pipeline, which resumed limited flows in late September 2025 after a two-and-a-half-year halt. Kurdistan’s fields are expected to produce 240,000 barrels per day, with 190,000 exported via Turkey and 50,000 allocated for domestic use.

Oil exports from the Kurdish Region were halted following an international arbitration ruling in March 2023 that found Turkey liable to the Iraqi government in Baghdad for allowing independent Kurdish exports; reportedly the arbitration ruling came with roughly $1.5 billion in damages exposure. Turkey more recently has publicly confirmed the resumption of oil, presumably in coordination with Baghdad.

Turkey is Iraq’s top trading partner. In the first six months of 2025, bilateral trade stood at $6.9 billion, $5.6 billion of which were Turkish exports to Iraq. Turkish companies are visible throughout the Kurdish Region of Iraq, especially in infrastructure construction. Ankara’s diplomats highlight over $35 billion in cumulative projects by Turkish firms across Iraq.

Ankara couples this economic weight with security conditionality. In August 2024, Turkey and Iraq signed a memorandum on military, security, and counter-terrorism cooperation, formalizing coordination against the PKK and normalizing aspects of cross-border activity. Turkish leaders have linked pipeline and trade facilitation to Iraq’s posture on the PKK, while engaging in occasional counterterrorism operations against the PKK and discussing a deeper security belt inside northern Iraq.

Water has emerged as a new lever of influence. President Erdoğan has reportedly linked improved water releases from Turkey’s Euphrates and Tigris dams to Baghdad’s willingness to confront the PKK – a “water-for-PKK” bargain.

Tehran’s Coercive Reach

Tehran wields its influence through security and political pressures as well as crossborder economic activity.

Trade remains a critical lever. Despite crippling US and international sanctions, Iran–Iraq trade reached nearly $12 billion in 2024, with the Kurdish region accounting for 40 to 60 of it through the Kurdistan Region’s eastern crossings. Iranian officials reported a 31 percent surge in goods transit through Parviz Khan during the first nine months of 2025. .

The Kurdistan Region and Iran share three official international border crossings, Parwez Khan in Garmiyan, Haji Omaran in Erbil, and Bashmakh in Sulaimani, as well as semi-official gates at Shushme, Sayranban, Kele, and Pishtay Tawela. Nawzad Sheikh Kamil, Director General at the Kurdish Region’s Ministry of Trade and Industry, announced that in 2023 more than 1,000 to Iranian entrepreneurs were issued business licenses; Iranian businessmen have begun expanding joint ventures with Iraqi partners based in Erbil and Sulaymaniyah.

Energy dependence further cements Iran’s leverage. In March 2024, Iraq signed a five-year deal to import Iranian gas – up to 50 million cubic metres per day – to meet the needs of its power stations. Iranian gas now covers nearly a third of Iraq’s electricity generation, giving Tehran an effective choke-point over Baghdad and by extension Erbil. This interdependence gives Tehran a strategic instrument of coercion; at moments of political friction, it can cut gas flows or delay electricity exports.

Economic leverage is reinforced by coercive force. On 15 January 2024, Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps fired a volley of ballistic missiles into Erbil, killing four civilians and claiming – falsely, according to both Baghdad and Erbil – that the attack had struck an Israeli “spy headquarters.” The attack sent a clear message of Iranian capacity and intent to use force on its neighbor.

On the political front, Iran exercises influence through partnerships with various Iraqi parties and armed factions, particularly through control of so-called “resistance groups” operating near the Kurdish region in areas of Iraq such as Kirkuk, Makhmour, and Sinjar. Under the 2023 Iran-Iraq security agreement, Baghdad pledged to crack down on Iran’s Kurdish opposition groups based in the Kurdish Region.

Competing Blueprints for Influence

Turkey’s ties run through the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) in Erbil and Duhok (led by the Barzani clan), while Iran maintains a parallel relationship with the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) in Sulaymaniyah (led by the Talabani family) – turning the Kurdish Region’s internal divide into an extension of their regional rivalry.

Beyond these political/clan alignments, both Ankara and Tehran are advancing competing infrastructure visions for Iraq.

Ankara’s Development Road Project, a $17 billion initiative linking the port of al-Faw in southern Iraq to the Turkish border, seeks to turn Iraq into a transport hub between the Gulf and Europe. Backed by Qatar and the UAE, the project positions Turkey as a gateway for Gulf trade and a counterweight to Iran’s corridors. It also deepens Ankara’s stakes in northern Iraq, where stability in the KRI is vital for keeping the route secure.

Tehran, which is excluded from the Development Road, is advancing its own version: the Shalamcheh-Basra Railway, a 32-kilometer line linking Iran to southern Iraq and eventually to Syria’s Mediterranean ports. Framed by Tehran and Baghdad as a rail to carry millions of Shi’i’te pilgrims to Najaf and Karbala, the Shalamcheh–Basra line is also cast by Iranian leaders as a first step toward a corridor to Syria’s Mediterranean ports, effectively a strategic land bridge for Iran.

Together, these projects turning transport infrastructure into an instrument of regional power.

Conclusion

In this fragile balance, the Kurdistan Region’s survival depends not on declaring allegiance to either one of its neighbors but rather to its ability to manage dependence on both. Erbil’s management of these rival powers – in addition to maintaining close ties to its national capital in Baghdad – will ultimately test the proposition of whether or not a small actor can retain agency when regional powers turn connectivity itself into an instrument of control.