On December 4, 2025, President Donald Trump presided over a signing ceremony at the US Institute for Peace for a peace agreement between the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda, the Washington Accords for Peace and Prosperity. Secretary of State Marco Rubio added that “we look forward to turning the agreements that we will be signing here today into reality.”

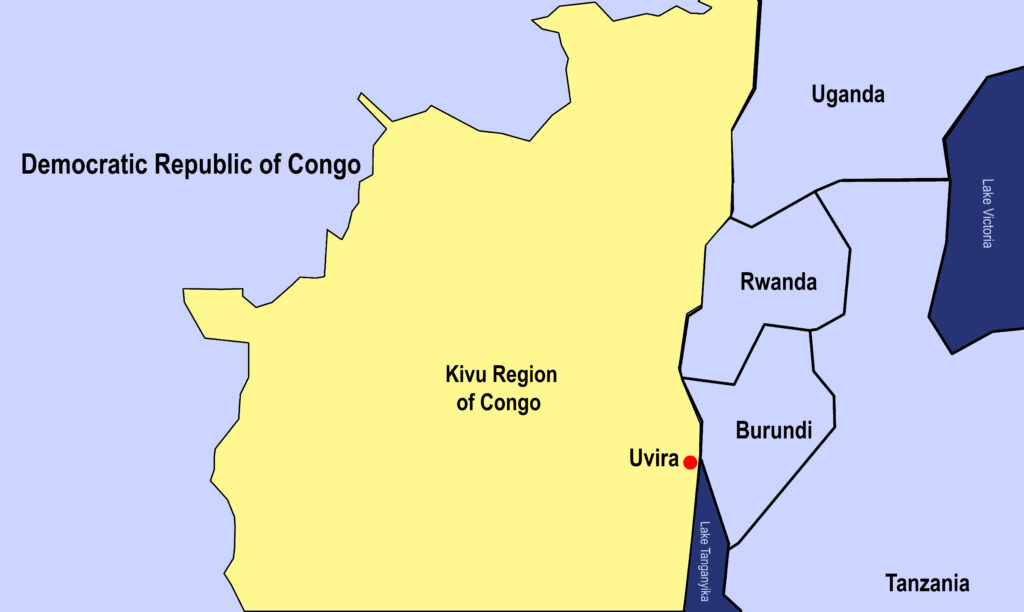

But conflict has returned. Tutsi rebel forces in eastern Congo (the “March 23 movement” or M23) withdrew as agreed from Uvira, but Congolese forces attacked them. In a December 18, 2025 post on X, Senator Lindsey Graham described himself as disheartened and warned “It is critical the United States maintains its leadership role.”

Fueling the conflict is incitement of ethnic hatred. On December 27, 2025, the official spokesman of Congo’s army warned Congolese on state television not to marry Tutsi women and called Tutsis “perfidious.” Other advisors of Congo’s President Félix Tshisekedi have called Tutsis cockroaches, snakes, and poison to be eliminated. Such speeches are reminiscent of Hutu rhetoric that culminated in the 1994 genocide in neighboring Rwanda.

Background on the Conflict

Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of Congo were relatively tranquil until European colonization. Each hosted kingdoms, complex societies, and a diverse array of trading tribes. There were squabbles but, generally, the region was peaceful.

The roots of the present-day conflicts began when Germany and, after World War I, Belgium took control over Rwanda and Burundi. Tutsis traditionally ruled the region and herded cattle, while Hutus were farmers. It was more a social distinction than a genetic one. Germany and Belgium’s introduction of eugenics, however, imposed a genetic component onto the tribal divisions and ossified them. Out went the social mobility; in came racial incitement. Hutu populists described the Tutsis as Nilotic interlopers who had no right to be in the region and who should return to the highlands of Ethiopia, from which they suggested the Tutsis had originated.

In the Rwandan context, the now racialized conflict led to the 1994 anti-Tutsi genocide. While Paul Kagame’s Rwandan Patriotic Front pushed the Hutu génocidaires across Rwanda’s borders into the Democratic Republic of Congo and Burundi, Hutu militancy festered as the United Nations allowed Hutu armed groups to take over refugee camps and indoctrinate a new generation of Hutus into the most virulent anti-Tutsi ideology. Rather than bring peace, the UN missions have cultivated hatreds.

Ethnic Conflict in The Democratic Republic of Congo

Felix Tshisekedi, the son of opposition leader and three-time Zairian prime minister Étienne Tshisekedi, came from a pedigree always close to power. When Joseph Kabila, also the scion of a political family whose father was president, announced he would not run for president in 2018, Tshisekedi became the front-runner.

The problem was he did not win the 2018 elections. Most election monitors and diplomats believe Martin Fayulu, a member of the National Assembly, did. Observers from the Catholic Church in Democratic Republic of Congo mobilized across the country and estimated Fayulu won 60 percent of the vote. Following the vote, however, Tshisekedi allegedly paid off parliamentarians and others to affirm his victory. Fearing violence, the international community accepted Tshisekedi and, in January 2019, he became the fifth president of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

During this period 2019-2023, relations between Rwanda and Congo thrived. Security forces cooperated and shared intelligence to stabilize the previously restive Kivu regions. Trade flourished. As Tshisekedi approached re-election in 2023, however, he faced a problem: infrastructure was crumbling and corruption had worsened. To distract the public, Tshisekedi incited ethnic unrest. Tutsis have lived in eastern Congo for hundreds of years, long before Belgium’s King Leopold II seized it. Yet, as Tshisekedi’s campaign floundered, he began voicing virulent conspiracies and questioning the legitimacy of any Tutsi presence in Congo. Night letters were tacked onto Tutsi homes, warning them to leave or suffer consequence. Some did. Local militias killed men and raped women who remained.

As the region descended into violence, Tshisekedi claimed inability to restore order and then blamed Rwanda for targeting those promising to overrun the country and resume the genocide. But if the Congolese military could defeat local militias and maintain stability in Katanga, in order to allow Chinese exploitation of cooper and germanium, they should be able to rein in mob violence in another part of the country, Kivu.

One problem for the US is it lacks diplomats who could travel to eastern Congo and gather firsthand information; instead it relies on local interlocutors or UN officials, many of whom also are stationed more than a thousand kilometers away and only gather secondhand information. Many Congolese cannot separate themselves from their own personal biases. If someone looks Tutsi then they are assumed to be Rwandan, not native to Congo. This is one of the reasons why, despite wild tails of Rwandan forces invading the region, the Congolese government has failed to produce a single Rwandan prisoner or body of slain Rwandan soldier.

What Congo needs now is a national dialogue The US should demand that Tshisekedi release political prisoners and the US should also condemn those who preach genocide against Tutsis. Absent addressing this commonsense approach, the Rwanda-Congo peace will be short-lived. There cannot be peace in the Congo without first ending anti-Tutsi incitement.