Maximum Pressure Is a Strategy — Not a Spectacle

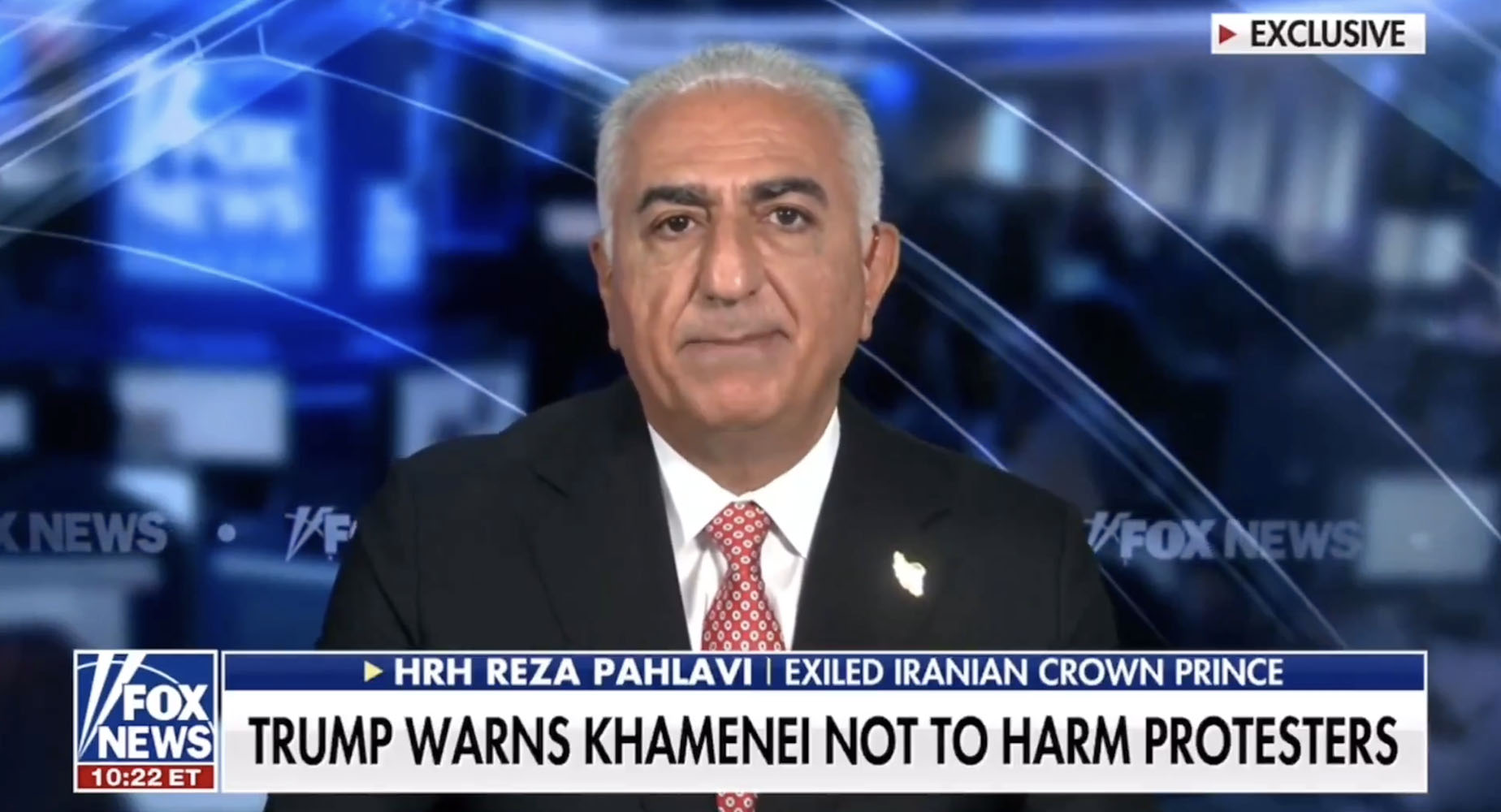

In a recent interview with Maria Bartiromo on Fox News, Reza Pahlavi — son of the late Shah of Iran — spoke about the brutal repression inside Iran, where protesters are executed, dissidents are silenced, and a generation lives under the constant shadow of state violence. He suggested that while diplomatic processes unfold abroad, the Iranian people continue to pay the price at home — an implicit criticism of the pace and nature of international engagement with this odious regime.

He also reiterated his readiness to play a role in a post–Islamic Republic transition and stated that the Iranian people should ultimately determine whether their future system would be a monarchy or a republic. The interview was less significant for what it challenged than for what it left undefined.

It revealed why the United States — and key figures in Washington — have maintained strategic caution regarding formal endorsement of any single opposition figure. The issue is not sympathy. The issue is structure. Let us be precise about what is unfolding.

The United States has positioned the USS Abraham Lincoln carrier strike group in the region. It represents the highest level of conventional deterrence short of direct military engagement.

Iran has rarely faced this degree of synchronized pressure. Military posture, however, forms only one pillar of the strategy.

Senior envoys — including Jared Kushner and Steve Witkoff — have engaged in sustained high-level shuttle diplomacy across continents. Thousands of miles traveled are not symbolic gestures; they are part of a coordinated effort to increase leverage, align regional actors, and press Tehran toward a framework that could ultimately benefit the Iranian population rather than the ruling elite.

This reflects a sophisticated balance of deterrence and inducement — the classic “carrot and stick.” Economic pressure constricts the regime’s maneuverability. Military positioning reinforces credibility. Diplomatic channels offer an exit ramp — but only under conditions that alter behavior.

Sanctions, force projection, and negotiation are not contradictions. They are components of a single strategic architecture. This is not passive negotiation. It is calibrated pressure. Pressure is method, and method requires time. But weakening a regime is only half the equation. The other half is building what comes next.

Transition Requires Conviction — Not Ambiguity

The central question facing Iran is not whether the current regime can be pressured. It is what replaces it.

Iran is an ancient civilizational state composed of Persians, Kurds, Azeris, Arabs, and Baluchis; Muslims of different traditions, Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians. Its identity predates the Islamic Republic by millennia. Transitions in such nations require reform — but they also require continuity.

Prince Pahlavi has stated that the Iranian people should decide between monarchy and republic.

At first glance, this appears democratic and generous. But leadership is not only about offering options. It is about embodying a clear institutional vision.

A generation of young Iranians has never lived under the Pahlavi era. For them, monarchy is not memory — it is abstraction. It exists in documentaries, in exile narratives, in fragments of history. If the very heir of that legacy presents it as merely one optional possibility among others, what message does that send?

If the Prince himself does not fully assume the institutional meaning of his heritage — if he treats monarchy as negotiable rather than foundational — how can he expect young Iranians to see it as a credible anchor for the future? Trust in leadership requires conviction that instills hope rather than uncertainty and fear about the future.

A republican model emerging from ideological collapse may risk fragmentation in a society marked by complex identities and regional dynamics. A modern constitutional monarchy, by contrast, can offer stabilizing architecture: a non-executive head of state embodying national continuity; an elected government exercising executive authority; a modern constitution protecting civil liberties and minority rights; a clear separation between national identity and partisan political competition.

Monarchy and democracy are not necessarily contradictions in terms. Some of the world’s most stable democracies—England , Sweden, Norway or Spain–function within constitutional monarchies that serve as unifying anchors above politics. Such a framework must be defended with clarity.

Young Iranians today are not asking for symbolic gestures. They seek dignity, opportunity, and integration into the modern world. They want access to technology, artificial intelligence, entrepreneurship, academic exchange, and global markets. They want freedom of movement. They want to welcome the world without sanctions or isolation.

They want, in short, to live in freedom rather than under the tyranny of a small clique of ideological fanatics who have warped their country’s destiny to serve their own interests.