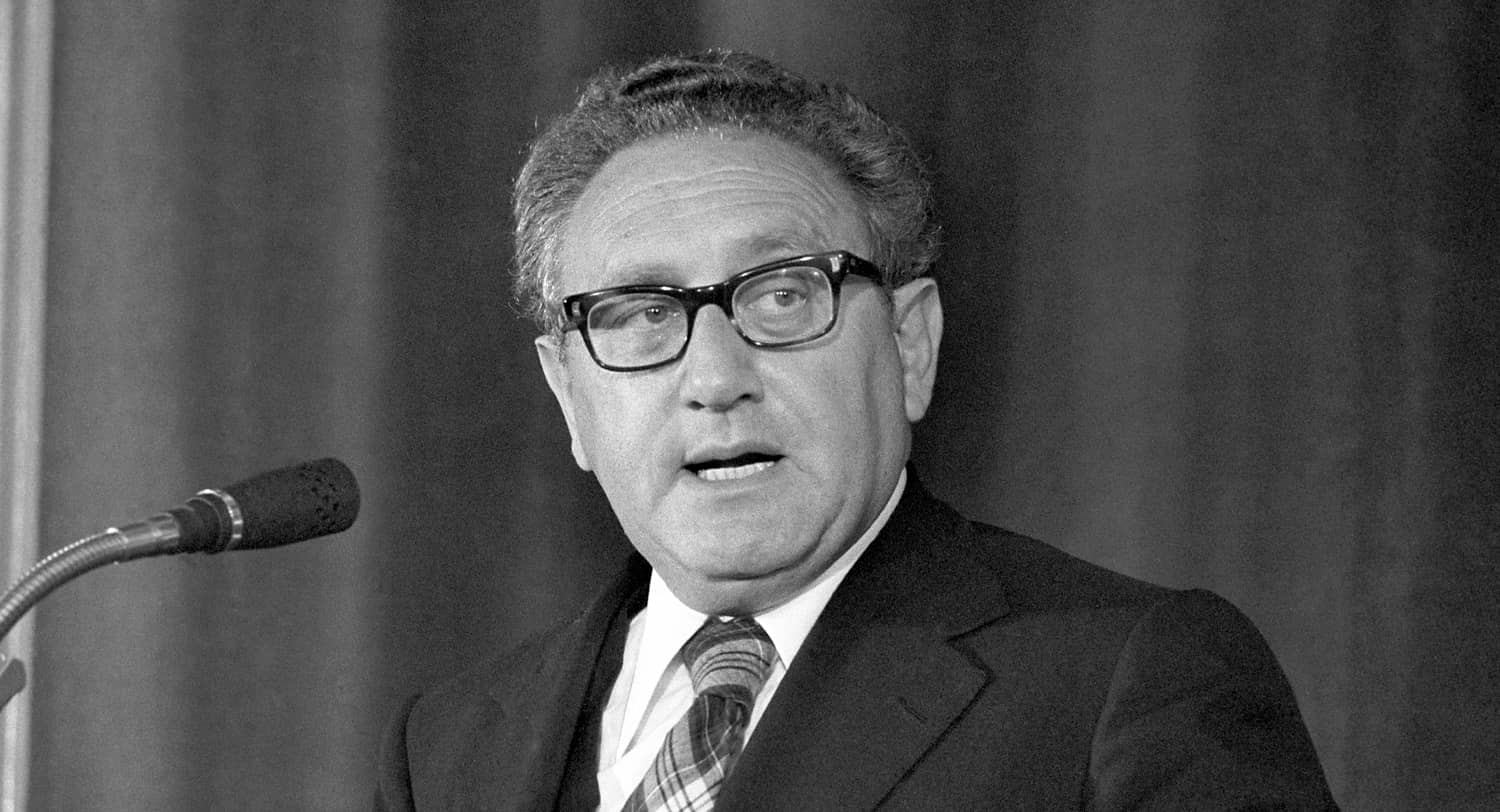

Kissinger, a PBS documentary by Barak Goodman, October 2025

PBS’s three-hour documentary on Henry Kissinger is in most respects admirable and should be viewed by everyone. Kissinger’s long life and exploits are handled briskly but thoroughly; the narrative does not dawdle, dramatic footage and scores of brief interview excerpts keep the story moving, quite coherently given the range of events covered.

Perhaps most important, the production portrays Kissinger as a foreign policy actor without peer in American history, with extraordinary impact in his active years and lasting influence through his achievements in office and relentless public engagement thereafter. What it does not do, however, is truly assess his role in the Cold War at the strategic level.

Balanced on Specifics

PBS labors to be balanced about Kissinger. It compares favorably to the ocean of attacks on Kissinger over the decades. Two recent egregious ones were the Ben Rhodes obituary in the New York Times, and a Washington Post piece at the time of his hundredth birthday highlighting dismay that the evil Kissinger had made it that far.

The production credits many specific accomplishments, and balances many criticisms (for example, that he allowed the Vietnam War to continue too long when allegedly “lost,” fomented upheaval in Cambodia, Chile, and Pakistan, betrayed American moral values) with explanations from biographers, former staffers, and his son David, of why Kissinger did what he did. This is so rare in other assessments. In particular, PBS has commentators note that for Kissinger, preserving American and Western security itself was the core moral value. Still, the series devoted considerably more time to criticism than to praise.

Cambodia was handled in a balanced way. Former staffer Winston Lord’s exasperation in responding to allegations of supposedly illegal military operations in Cambodia was priceless. In sum, he said: come on, the North Vietnamese Army had invaded Cambodia, was attacking our forces and killing Americans from it and retreating back to it as a safe haven, so of course we attacked them.

Unfortunately, the program left unchallenged the assertion made by one Cambodian, and held by many Americans, that supposedly the Khmer Rouge’s evolution from minor force to genocidal victors was the result of the US bombings and incursion. This idea that American decisions and actions can change the trajectory of whole states and societies, while prominent on the Left, was never one of Kissinger’s beliefs.

In the case of Vietnam, Winston Lord noted it was only in fall 1972, not in 1969, that Hanoi dropped its non-negotiable, unacceptable demand that the US not only leave but dismantle the “puppet” South Vietnamese government. Both Kissinger and his son are eloquent in arguing that the 1975 fall of South Vietnam was his worst moment in government. Contrary to the accusations that he merely wanted a “decent interval,” Kissinger believed that if Congress had not blocked Washington’s resupply and air support commitments Saigon could have beaten back the 1975 Hanoi offensive. (This writer, having witnessed the South Vietnamese Army do just that in the 1972 Hanoi Easter offensive, agrees.)

On Chile, the documentary detailed Kissinger and Nixon’s direct involvement in the 1970 coup attempt. But unlike many accounts the program argues there is no evidence that the US, or at least Kissinger, knew in advance of the 1973 coup that overthrew Allende.

But Adrift on a Strategic Assessment

What is lacking in the piece is a deeper analysis of the strategic-historic context of both Kissinger’s achievements and his alleged disregard for human rights values and the link between them. Kissinger biographer Niall Ferguson is quoted that we are all “in Kissinger’s world now,” but the production does not attempt either to flesh out or challenge that assertion.

That absence perhaps reflects a general American tendency to deal with factual specifics not more theoretical big pictures (Kissinger himself being an exception to the tendency). Still, the piece should have been clearer, explaining the strategic context of Kissinger’s work, analysing, drawing on examples from other administrations, of how the “agonizing options” were handled, and judging overall strategic success and failure.

In fact, such agonizing decisions were commonplace in the Cold War and afterward, and not solely Kissinger’s. The Truman Doctrine undergirding Greece, Turkey and Iran, and the defense of Korea and Taiwan in 1950, were all in support of then undemocratic states, with the arguable exception of Greece. In 2022 President Biden embraced the same approach in his National Security Strategy, stating that the US will partner with “countries that do not embrace democratic institutions but nevertheless … support a rules-based international system.” Kissinger couldn’t have said it better.

In the end, the United States won the Cold War, first helping flip China in 1972. And twenty years later the Soviet Bloc collapsed. Thus containment policy worked. But to work, it had to spread its shield over not only democratic states like Denmark but the gaggle of often hapless, oppressive dictatorships, monarchies, and military regimes that made up most of the states along the Soviet and Chinese perimeter.

What PBS Missed

Not only did Kissinger embrace with gusto that approach, but he achieved a degree of strategic success that certainly strengthened America’s position in the Cold War, and arguably fended off a communist victory. 1968, as the series makes clear, was America’s nadir in the almost fifty-year Cold War. America had suffered if not a battlefield, then a huge political defeat in Tet, the country was falling apart, the entire containment strategy under assault, with the streets ablaze and a president quitting.

Within six years, thanks to Kissinger and Nixon, the strategic picture was vastly different. In the Far East, Communist China had flipped from enemy to quasi-partner, and the Asian periphery had held, as Singapore’s then Prime Minister Lee has stressed, because America stayed the course in Vietnam and elsewhere long enough for those states to stabilize and China to cease its direct and indirect aggression.

In the Middle East, the US had saved what was to become its most important ally, Israel, from defeat in the Yom Kippur War, then transformed Egypt from enemy to ally, largely excluding Moscow from the region. And in Europe, with the SALT nuclear accords with the USSR, and the 1975 Helsinki Final Act, a new stable status quo emerged ultimately fatal to the Soviets.

Lasting Divide in the Foreign Policy Community

PBS may have avoided such an assessment because diving into it would have required entering a minefield dating back fifty plus years and still active, involving a still-unhealed split in America’s foreign policy community. This point is central to comprehend American foreign policy generally, and the treatment of Kissinger specifically.

The divide goes back to the turbulent sixties, even more polarized and violent than today’s America. From the 1940’s until roughly 1967, the American foreign policy community shared a common foreign policy dogma: containment, a continuation of the “avoid domination of the Eurasian world island by a hostile entity” policies of Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt, through a military-based collective security strategy along with various economic and political principles as appendages.

But by 1967 that dogma was severely challenged by the more progressive wing of the foreign policy community, composed of university communities, students, most media, foundations, many think tanks, much of civil society, and to some degree the Democratic Party and Congress, all involved in the business of shaping public views on foreign policy. They took a more stridently antiwar view towards Vietnam and later to containment generally.

The other wing, governance (the administration, military, diplomatic service, part of Congress, and some trusted outside advisors) also viewed Vietnam increasingly as a failure, including Henry Kissinger, as the PBS documentary clarifies. But it was a failure of application in the field, with General Westmoreland and Secretary of Defense McNamara, not of containment theory. As PBS reports, Kissinger as an advisor wrestled with this. “Need a negotiated settlement, but cannot simply walk away with so many troops committed.” That is, find a way out but not at the expense of containment’s core component, American credibility, which Kissinger often described as “honor.”

For those opposed to Nixon and Kissinger, containment itself, not just its application in Asian jungles, became the problem, a view long held by pundit-in-chief Walter Lippmann, and given national prominence in the 1967 Senate Foreign Relations Committee Vietnam hearings chaired by Senator Fulbright.

Their proposed alternatives to containment were amorphous but focused on deemphasizing military force. (Their champion George McGovern’s “Come Home America” theme was directed at soldiers.) In addition, human rights, internationalism, global values and diplomacy were embraced. Essentially, they rejected the lessons of the 1930’s in favor of an untested theory that all international conflicts were the results of misunderstandings and insecurity, with the remedy being not Kissinger’s muscular policies but trust-building, negotiations, and above all military de-escalation.

For example, Kissinger critic Roger Morris and others repeatedly argue that Kissinger’s focus on credibility/honor cost many lives. True, but it also saved them. In the Yom Kippur War the Soviets mobilized troops to intervene. Nixon and Kissinger then placed the entire US military on DEFCON Three war readiness. Within hours Moscow backed down, having seen that this Washington, with actions like the Hanoi Christmas bombing, should not be toyed with. That ended the war and defused a potential Cuban Missile Crisis-level confrontation. Strangely, or perhaps not, PBS did not cite this most dangerous but arguably most triumphant moment of Kissinger’s tenure.

Fortunately for global stability and American security, the progressive viewpoint never captured the governance wing of the foreign policy establishment, with the exception of the early Carter administration (his 1977 speech warning of an “inordinate fear of communism”) and occasionally thereafter (Obama’s Syrian “red line” choke of 2013). But that viewpoint has remained strong among many Americans, influencing congressional decisions (for example, the 1974 blocking of assistance to an embattled Saigon, three Senate roll call votes required in 1991 to endorse liberating Kuwait).

Never to be Forgiven

The problem for Kissinger and his legacy is that he (and Nixon) successfully defied this progressive catechism almost as soon as it was created. PBS cited Nixon’s 1972 electoral win only in passing but in fact it is vital to American foreign policy history.

The 1972 election represented a stinging rebuff by voters (in 49 of 50 states) to the progressive worldview and its candidate who apparently confused college students and New York Times subscribers with the American people. Nixon and Kissinger after all had escalated dramatically in Vietnam a few months earlier in response to the North Vietnamese offensive. Their support for Pakistan in the Bangladesh war, the attempted 1970 coup in Chile, and military operations in Cambodia were all in the public domain. Also, as promised, they had brought home 90 percent of the troops without defeat.

By the end of the Kissinger era, that impressive Cold War edifice described above was in place, and thirteen years later, final victory achieved, through Kissinger’s strategy as followed by Reagan and Bush. Kissinger had shown definitively that power, including military force, along with negotiating flexibility, can achieve stability, peace and victory.

Many still remain wedded to that progressive worldview (most recently seeing the Israeli regional strategic victory of 2023-25 in terms only of a “genocide” in Gaza). Kissinger by proving them wrong has become an outcast, condemned in many circles as a “war criminal.” And thus PBS, while trying commendably to give balance to both sides, but faced with all this, ducked the job of providing a serious assessment of Kissinger’s historic role.

One flaw of the production was not interviewing American soldiers, who were so impacted by Kissinger’s actions and who ultimately contributed to his successes. So let’s give the last word to one of them, the writer’s boyhood friend, former Lieutenant William Golden, deep in the bush with a Vietnamese unit in 1970: “I felt like I was on two separate tours, one, whew, before the 1970 Cambodian incursion, and then everything went quiet thereafter.” I am sure that former Sergeant Henry Kissinger, 84th Infantry Division and Battle of Bulge veteran, would have been touched.