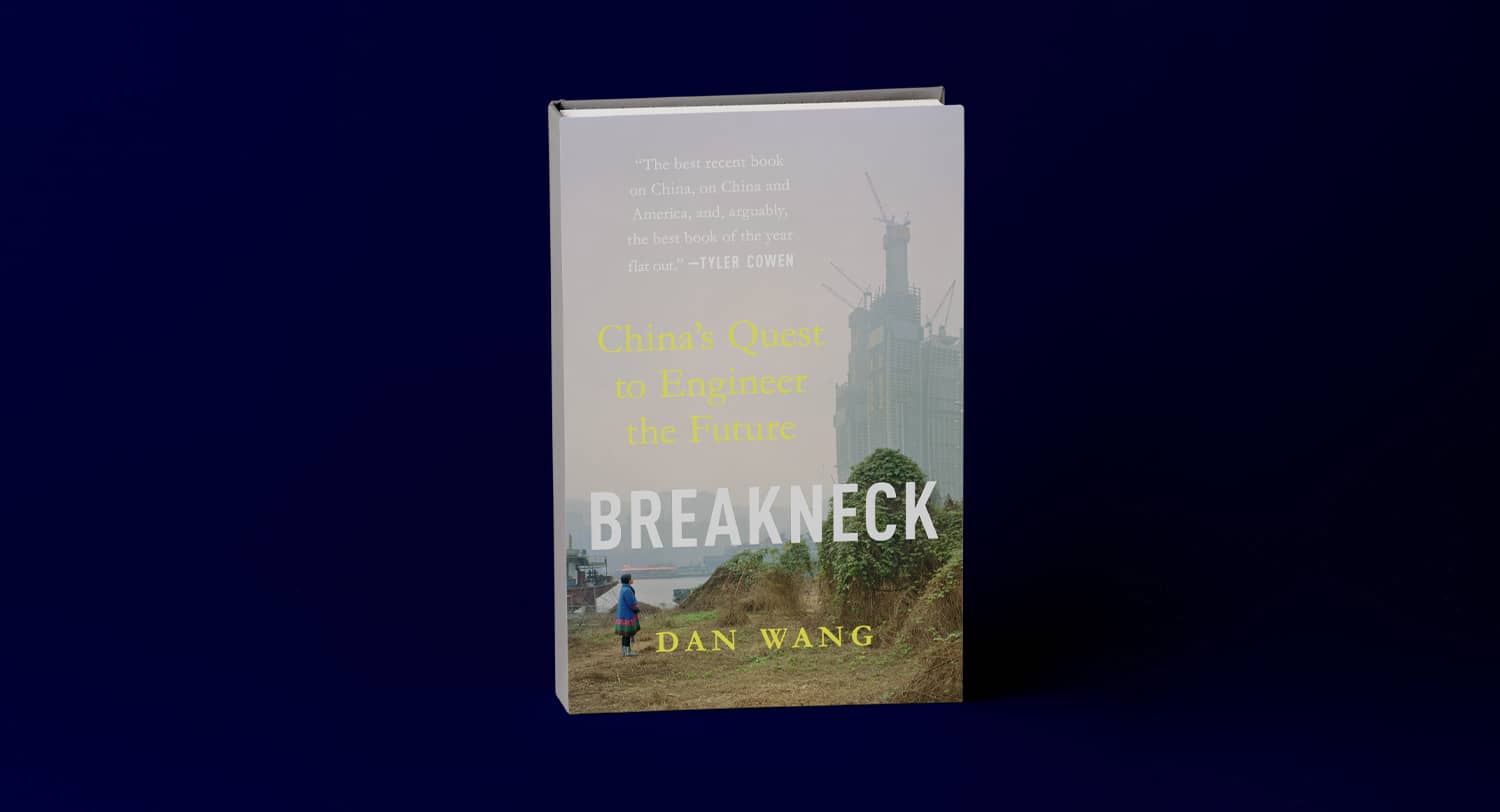

Dan Wang, Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, W.W. Norton, 2025

The familiar typology of political systems comes to us from the ancient Greeks, who coined terms to describe the source of effective power. Thus, the United States counts as a democracy, with power vested in the people, the demos, while China may be termed an autocracy – rule by the self, that is, a single person — in the Chinese case the leader of the country’s ruling Communist Party.

There are other ways to distinguish among regime types, and in his book Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future, Dan Wang proposes a useful one. He emigrated from China to Canada with his parents at the age of seven, received his education in the United States, and spent six years in Hong Kong, Beijing, and Shanghai as an analyst of Chinese economics and politics. He knows both America and China well. He calls China an engineering state and America a lawyerly society, terms that help to describe their strengths and weaknesses, to explain their achievements and failures, and to predict their likely futures.

The two terms have a literal application: most of China’s leaders have had some training in engineering, while a large proportion of the American political elite attended law school. The distinction also illuminates differences in the styles of governance and the results of those styles in the world’s two most powerful countries. Engineers work in concrete and steel, lawyers in words, typically in the form of briefs and petitions. Engineers focus on material outcomes, lawyers on procedures. Most importantly, engineers build things while lawyers do not.

Over the past four decades, China has built on a colossal, historically unprecedented scale. It is now richly endowed – in many respects better endowed than the United States – with roads, ports, dams, airports, and railroads. Americans familiar with their country’s history will recognize that a hundred years ago the United States also built such things on a large scale. To coin a phrase, That Used To Be Us. Now, construction of American infrastructure proceeds painfully slowly and on a small scale, when it proceeds at all. Wang cites a vivid example of the difference.

[In 2008] California voters approved a state proposition to fund a high-speed rail link between San Francisco and Los Angeles; also that year, China began construction of its high-speed rail line between Beijing and Shanghai. Both lines would be around eight hundred miles long upon completion.

China opened the Beijing-Shanghai line in 2011 at a cost of $36 billion. In its first decade of operation, it completed 1.35 billion passenger trips. California has built, seventeen years after the ballot proposition, a small stretch of rail to connect two cities in the Central Valley, neither of which are [sic] close to San Francisco or Los Angeles. The latest estimate for California’s rail line is $128 billion.

The Shanghai-Beijing rail link illustrates the advantages of China’s engineering state. More generally, the country’s 40-year building spree has helped to lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, making it arguably the most successful anti-poverty program in human history. The American system, too, has strengths: it allows for changes of course that can avoid costly errors of policy and protects individuals and groups of citizens from harmful consequences of government policy, as China’s engineering state, which functions as an unstoppable bulldozer once its course is set, does not.

The history of California’s ill-fated Los Angeles to San Francisco fast train makes clear the downside of America’s lawyer-dominated political system. Two acronyms express its defects: NIMBY – “not in my back yard” – refers to the tendency of Americans, especially wealthy ones, to prevent projects of which they approve in principle, sources of renewable energy, for example, from being located near where they live; and BANANA – “build absolutely nothing anywhere near anything” – is self-explanatory. Still, China’s engineering state, for all its visible and dramatic achievements, has negative effects as well, and Wang devotes most of his book to chronicling them.

He argues that China builds too much. It has put in place infrastructure that is little used and therefore uneconomical. It erected too much residential housing for even the most populous country in the world, leading to a housing bubble that has proven costly to unwind. In the Chinese system, local Communist officials get rewarded, above all with promotions, for shepherding building projects to completion, the more numerous and grandiose the better. Hence the proliferation of projects without regard for their ultimate economic viability. This is a poor use of the country’s resources.

In addition, China’s engineer-leaders are obsessed with manufacturing, and the country has duly become the leading manufacturer in the world. It produces far more manufactured products than are consumed at home, especially because China’s supreme leader, Xi Jinping, takes a dim view of consumption. As a result, China floods the world with what it makes.This, in turn, has caused a backlash in countries, and not only the United States, whose domestic industries the flood from China threatens. The Chinese regime’s strategy for economic growth depends on an ever-expanding volume of exports, but it is far from clear that other countries will continue to accept them.

China’s engineer-dominated political system has another deep flaw. In contrast to the United States, it does not respect the rights or interests of individual Chinese. It sets goals and then plows ahead to fulfill them, regardless of the cost to the Chinese people. Wang devotes a chapter each to two glaring examples of this feature of contemporary China: the policy of permitting married couples to have only one child, which began in 1980; and the restrictive lockdowns of large parts of the country’s population during the Covid pandemic. Both policies imposed enormous inconvenience and a good deal of discomfort: the one-child policy also occasioned instances of terrible cruelty.

While the engineering mindset that pervades the Chinese government may have had something to do with these episodes, each was also distinctly and characteristically communist. Both were nation-wide campaigns, decided at the whim of the supreme leader and implemented by government coercion, that caused widespread disruption and considerable suffering. In this way, they belong in the same category as the collectivization of agriculture in the Soviet Union and China as well as the Chinese “Great Leap Forward” of the 1950s, which caused as many as 40 million people to starve to death, and China’s “Great Proletarian Culture Revolution” of the 1960s, which threw the country into violent chaos. These campaigns came about at the behest of Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong, dedicated communist revolutionaries neither of whom was an engineer.

One consequence of the differences between the Chinese engineering state and the American lawyerly society has major, and for the West alarming, implications for international politics. The two countries are military rivals, each of whom is preparing for the possibility of a shooting war with the other. The likeliest cause of such a conflict is the status of the democratic and effectively independent island of Taiwan, located approximately 100 miles from the Chinese mainland. The Communist government in Beijing claims that Taiwan belongs under its jurisdiction, while the United States is committed – in fact albeit not by treaty – to protecting the island against a Chinese attack.

Wars are fought with military equipment and China makes far more of it, far more rapidly, than does the United States, even including the military production of America’s allies. “In 2022,” Wang writes, “China had nearly 1,800 ships under construction, and the United States had 5.” He quotes an American official as saying that, in a conflict with China, the United States would experience “the exhaustion of munition stockpiles very rapidly.” In this particular arena, that is, the Chinese system has a clear superiority over the American one. In a real war, engineers will beat lawyers every time.