With the Syrian state still in its formative stage, lacking a defined political identity, two Gulf monarchies – Qatar and Saudi Arabia – are seeking to dominate Syria. This competition will only intensify as the interim Syrian government of Ahmad al-Shara’a grapples with state-building.

Qatar provided a cash infusion on August 6, when its UCC Holding inked a $4 billion agreement with the Syrian government to construct a new airport in Damascus. The agreement, one of a dozen foreign investment deals signed that day, came on the heels of a $6.4 billion pledge from Saudi Arabia to support tourism, construct housing, factories, and skyscrapers, and develop the medical, telecommunications, and entertainment industries in Syria.

Saudi Arabia and Syria signed an “investment promotion and protection agreement” on August 19, which was followed by a second Saudi-Syrian investment conference on August 24 and the arrival of a Saudi business delegation in Damascus on August 26. The Saudi investments were followed by humanitarian relief projects sponsored by Riyadh that include “61 initiatives in the health sector, rehabilitation programs, orphan care, and overland aid convoys delivering essential supplies,” announced on September 8.

These recent announcements of financial commitments (not all of which will necessarily be realized, if past is prologue) are part of a larger international effort to rehabilitate a Syrian economy decimated by civil war and international sanctions. In May, Saudi Arabia and Qatar paid off Syria’s $15.5 million debt to the World Bank, paving the way for the World Bank Group “to reengage” with Syria and “address the development needs of the Syria people.” Weeks later, Qatar and Saudi Arabia announced “joint financial support” for public sector employees.

While Qatar and Saudi Arabia are cooperating on short-term priorities, their collaboration in Syria mustn’t be mistaken for a lasting partnership. The two monarchies have each sought to expand their regional influence politically and economically, often at each other’s expense.

The point of contention between them is political Islam. Qatar has actively promoted Islamist movements like the Muslim Brotherhood as a core part of its foreign policy, while Saudi Arabia under Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman considers the Brotherhood to be a threat to his kingdom’s stability, condemning the Brotherhood for fostering extremism.

Within days of Bashar al-Asad’s ouster, Qatar began reengaging with Damascus, working with Turkey to bolster the new Syrian government. Turkey and Qatar were the first and second countries, respectively, to reopen embassies in Syria. In January, Qatar’s Emir made the first visit by a foreign head of state to Damascus.

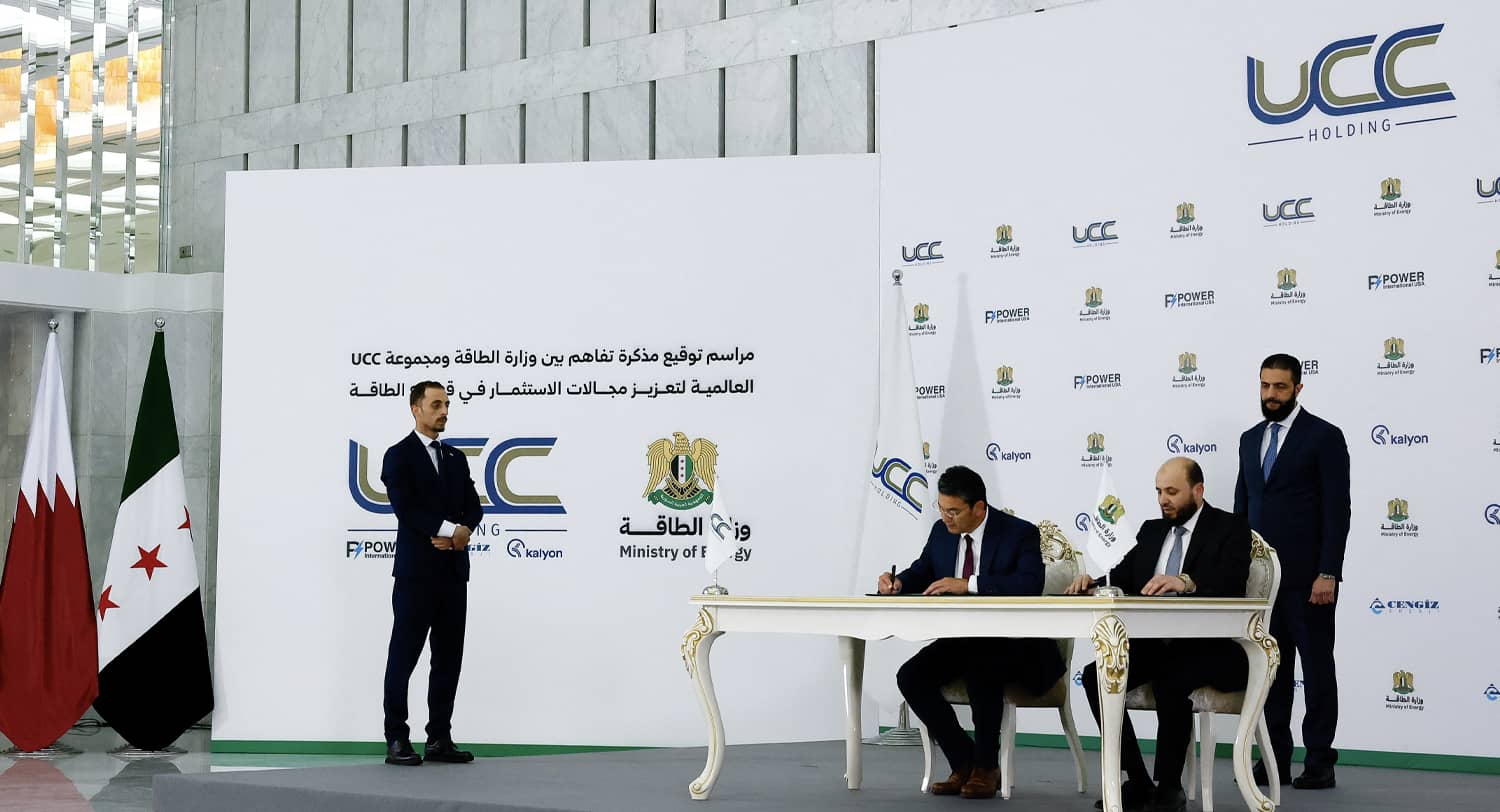

Qatar has followed up this diplomatic outreach by financing infrastructure projects in Syria, focused on restoring electricity. Qatar got the greenlight from Washington in March to begin pumping natural gas to Syria via Jordan. In May, Syria signed a $7 billion agreement with Qatar’s UCC Holding, Power International USA, and two Turkish energy companies to construct four power plants and a solar farm in Syria. The latest energy deal launched on August 2, when Qatar began financing natural gas deliveries to Syria from Azerbaijan via Turkey.

This summer has seen Damascus sign close to $2 billion in additional deals with Qatari companies. In June, the Syrian government signed a $1.5 billion agreement with a Qatar’s Al Maha International to establish a hub for “media, film, and tourism” in Syria called “Damascus Gate.” Qatari telecommunications firm Ooredoo is also in the running to build out Syria’s fiber optic communications network. The project’s price tag is roughly $300 million.

Qatar’s investments outweigh Saudi Arabia’s to date, but Riyadh has also provided key political support. In May, Crown Prince Muhammad bin Salman, joined by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, successfully lobbied President Trump to lift sanctions on Syria.

In July, a Saudi delegation met with interim Syrian president Ahmad al-Shara’a and hosted an investment forum, where the delegation announced significant infrastructure investments. This visit took place as sectarian clashes roiled southern Syria, signalling Riyadh’s support for Syria’s territorial integrity and positioned Saudi Arabia as a key protector of Syria’s interests, despite atrocities by government-aligned forces in southern Syria. Saudi Foreign Minister Faisal bin Barhan told Secretary of State Marco Rubio that Saudi Arabia supports the deployment of Syrian troops in the predominantly Druze province of Suwayda.

Saudi Arabia wants a stable Syria free of the Iranian influence that led the country to become a hub for both transnational terrorism and drug trafficking. Captagon from Syria placed a significant strain on Saudi Arabia. Its investments also aim to curb Qatari and Turkish influence and to prevent Syria from becoming a client state of either country.

Shara’a is currently playing both sides to extract maximum financial and political benefits. He understands that siding too heavily with one camp risks alienating the other—and losing valuable investment. This risk is particularly acute in the case of Saudi Arabia, which has a track record of withdrawing support when a country’s trajectory conflicts with Riyadh’s. For example, Lebanon fell out of Riyadh’s favor after failing to curb Iran’s influence. To prevent a similar fallout, Damascus has carefully distributed projects between both countries to sustain the competition between them.

The key question now is which ideological path Shara’a will embrace. Will he foster closer ties with the Muslim Brotherhood and align with Qatar? Will he distance himself from political Islam to reassure Saudi Arabia and prevent Riyadh’s potential withdrawal? Or will he continue to delay choosing an ideological path and play both sides?

Recent statements suggest Shara’a seeks to distance himself, at least rhetorically, from the Brotherhood despite his Islamist background. Shara’a may be aligning more closely with Riyadh, but that is unlikely to push Qatar out of Syria; instead, Doha will likely continue to invest in Syria, hoping to tilt Shara’a back into its orbit.

What should the US do? In the short term, it must monitor investment flows in Syria. The risk of investments enriching terrorist groups is high given that the Syrian government has integrated groups into its military that maintain active ties to foreign terrorist organizations such as al-Qa’ida. The military has also committed human rights abuses since coming into power, and Syria continues to host several designated terrorist organizations, including Katibat al-Tawhid wal-Jihad.

Despite removing most sanctions on Syria, Washington has not clarified whether there is a monitoring mechanism in place designed to track and prevent terror financing. Washington should press Syria to put such a mechanism in place and cooperate with groups such as the Financial Action Task Force, the intergovernmental watchdog for money laundering and terror finance.

Washington should also make clear to Shara’a that there is a window of opportunity for historic improvements in US-Syria relations. If he takes meaningful steps to protect minorities from abuse, holds perpetrators accountable, and restrains extremists, a new era can begin.