In October 1988, Russell Kirk, a founding father of the modern conservative movement, gave a speech at the Heritage Foundation that touched on America’s relations with Israel. “Not seldom,” Kirk said, “it has seemed as if some eminent neoconservatives mistook Tel Aviv for the capital of the United States — a position they will have difficulty in maintaining as matters drift.”

The neocons quickly gave as good as they got. Midge Decter, a member of the Heritage board, responded that Kirk’s talk was a “bloody piece of anti-Semitism.” And her husband, Norman Podhoretz, the editor of Commentary magazine, declared that Kirk may have been a venerable figure on the right, but that he had an “anti-Semitic stench.”

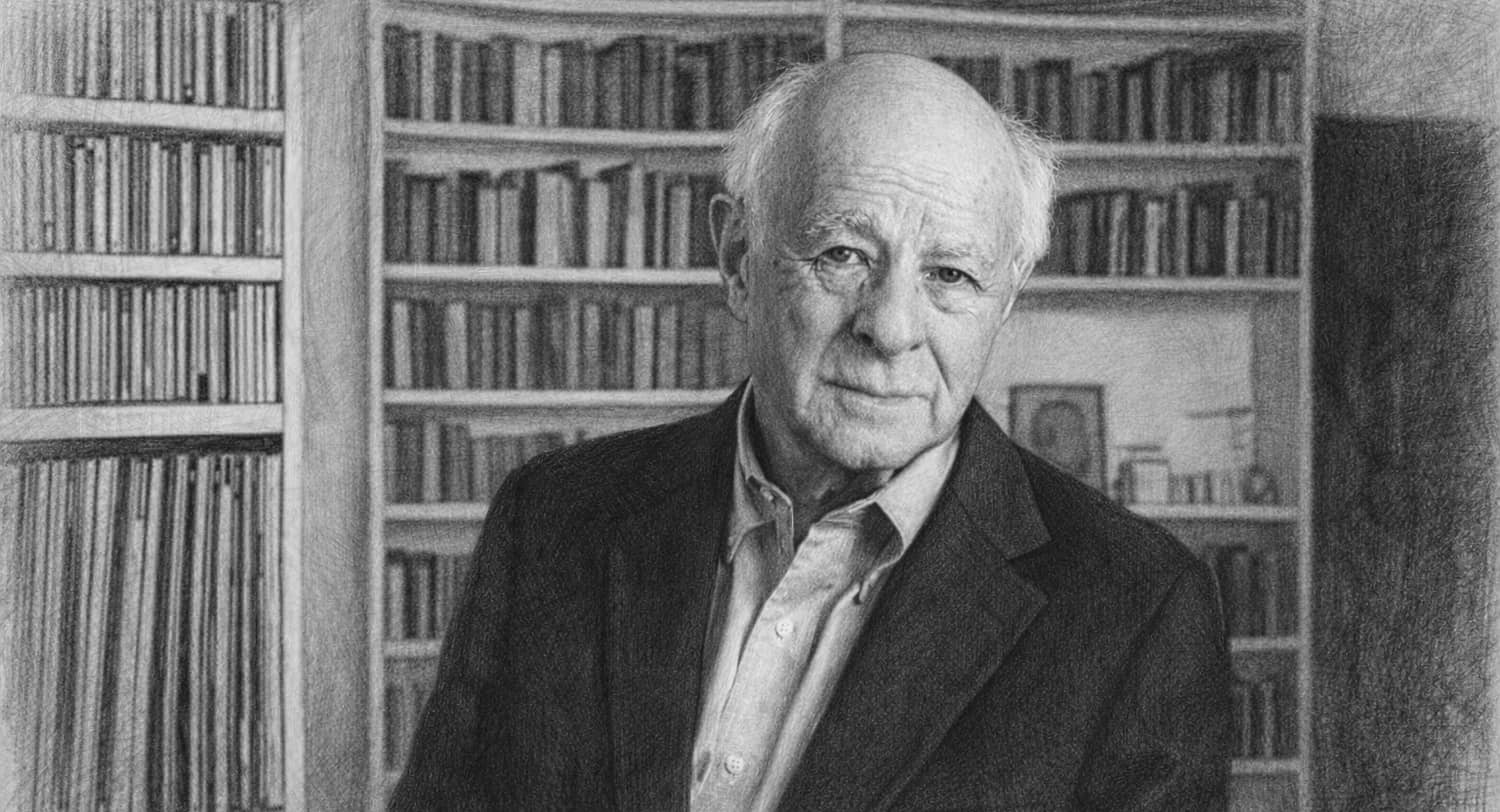

For Podhoretz, who died this past week at age 95, the antipathy to Israel from paleoconservatives such as Kirk and Patrick J. Buchanan represented a clear and present danger. Swatting aside the buzzing of liberals like Gore Vidal, who had accused Podhoretz of dual loyalty in the Nation, was one thing. Confronting skepticism about Israel on the right was another. It represented a threat to the standing of the neocons who had moved from left to right.

A key member of the New York intellectual family, Podhoretz had broken ranks by denouncing the rise of a leftwing counterculture and detente with the Soviet Union. He never looked back. Unlike numerous other neocons who morphed into Never Trumpers, Podhoretz proclaimed that Donald J. Trump possessed the ability to “save America from the evil on the left.”

Like neoconservative worthies Irving Kristol, Gertrude Himmelfarb, and Nathan Glazer, Podhoretz was born into an immigrant Jewish family. But there the similarities end. Podhoretz was born in 1930, a decade after Kristol and his cohort. What’s more, he did not attend meetings of the Young People’s Socialist League as a teenager or debate the merits of Trotskyism versus Stalinism. Instead, his formative interests were literary, not political.

The first in a series of mentors was his high school English teacher, Mrs. K., described in his memoir Making It as intent on fashioning an unruly charge into a young gentleman. “My grades were very high and would obviously remain so,” Podhoretz recalled, “but what would they avail me if I continued to go about looking and sounding like a ‘filthy little slum child’ (the epithet she would invariably hurl at me whenever we had an argument about ‘manners’)?”

At age 16 Podhoretz obtained a full scholarship to attend Columbia University, where he became a protégé of Lionel Trilling (who had himself become the first Jewish professor to secure tenure in the English department). Next Podhoretz attended Cambridge University on a Kellett fellowship, studying with the literary critic F.R. Leavis. An academic career seemed in the offing. In 1951, Leavis asked Podhoretz to review Trilling’s The Liberal Imagination in his quarterly, Scrutiny. But Podhoretz eventually decided that he was after bigger game.

Upon returning to America, he began writing for Commentary and the New Yorker. In 1960, Podhoretz became Commentary’s editor, a year after its founding editor, Elliot Cohen, the mentor of Lionel Trilling, had committed suicide.

He had arrived at a propitious moment. “The vogue for Jewish writers and intellectuals became so intense—their bylines in the major magazines and journals swarming so thick—that it even provoked occasional complaints from gentile writers that they were suffering exclusion by virtue of their non-Jewishness,” wrote Daniel Oppenheimer in Exit Right.

In 1968, Podhoretz made waves with Making It, which flaunted his ambition. “Do not publish this book,” Trilling said. “It is a gigantic mistake.” Actually, it was vivid, raw and fascinating. Reissued by New York Review of Books Classics, it presaged the rise of the confessional genre. But the public and private rejection of the book—the reviews competed to outdo each other in viciousness and Podhoretz was expelled from the New York intellectual family–sent its author hurtling into an emotional tailspin from which he only reemerged several years later.

In his new incarnation as a culture warrior, Podhoretz targeted the liberal left that he had once courted. In many ways, Podhoretz’s antipode was Robert Silvers, co-editor with Barbara Epstein of the New York Review of Books. But what he lost in social status among the Manhattan glitterati Podhoretz won in political influence. Together with Irving Kristol’s new publication The Public Interest, Commentary started to serve as the doctrinal fountainhead of the neoconservative movement. Having adopted the habiliments of a right-wing culture warrior, Podhoretz would never shed them.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Commentary became the little magazine par excellence, an intellectual outlet punching above its weight class. Podhoretz recruited a variety of top drawer intellectuals, including Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Walter Laqueur, Richard Pipes, and Jeane J. Kirkpatrick. Kirkpatrick’s 1979 essay on “Dictatorships and Double Standards,” which distinguished between the staying powers of authoritarian and totalitarian regimes, earned her a post as Ronald Reagan’s ambassador to the United Nations.

With his zest for political drama, Podhoretz kept moving steadily right. In his book Ex-Friends, Podhoretz wrote, “only among conservatives could I find genuine allies in the intellectual campaign I was now undertaking to help revive the American will to resist Soviet expansionism, a campaign against those in both major parties who were, as I put it in the title of an article I wrote in 1975, `Making the World Safe for Communism.’”

In 1982 he wrote an essay attacking Reagan for insufficient avidity in prosecuting the cold war, called “Appeasement By Any Other Name.” He was also skeptical of Reagan’s attempts to reach out to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. But Reagan saw what many neocons didn’t, that Marxism-Leninism Inc. was a faltering enterprise.

With the end of the Cold War, Podhoretz focused on the culture wars and defending Israel. He denounced Patrick J. Buchanan and the paleoconservative right for anti-Semitism.

Today, the controversies of the past have returned. When the Heritage Foundation’s president, Kevin Roberts, defended Tucker Carlson’s decision to give a sympathetic interview to Nick Fuentes, an anti-Semitic podcaster, John Podhoretz, son of Norman and Midge and current editor of Commentary, fought back. “My mother was on the Heritage Foundation board for 40 years. She loathed nothing more than intellectual inconsistency and transactional cowardice. Kevin Roberts, you should be shamed by the name and memory of Midge Decter, who would have known you for the fraud you are.”

A furor then erupted at the annual Turning Points USA youth conference in December. Ben Shapiro was mocked by Steve Bannon and Tucker Carlson for his defense of American ties with Israel and condemnation of the malodorous Nick Fuentes.

As the Republican party once more squares off over America’s support for Israel and intervention abroad, the battles of Norman Podhoretz have acquired a new virulence. Will the GOP post-Trump continue to endorse the vision that Podhoretz propounded? Certainly on Israel, President Trump shares that vision, meanwhile the debates within his party continue.