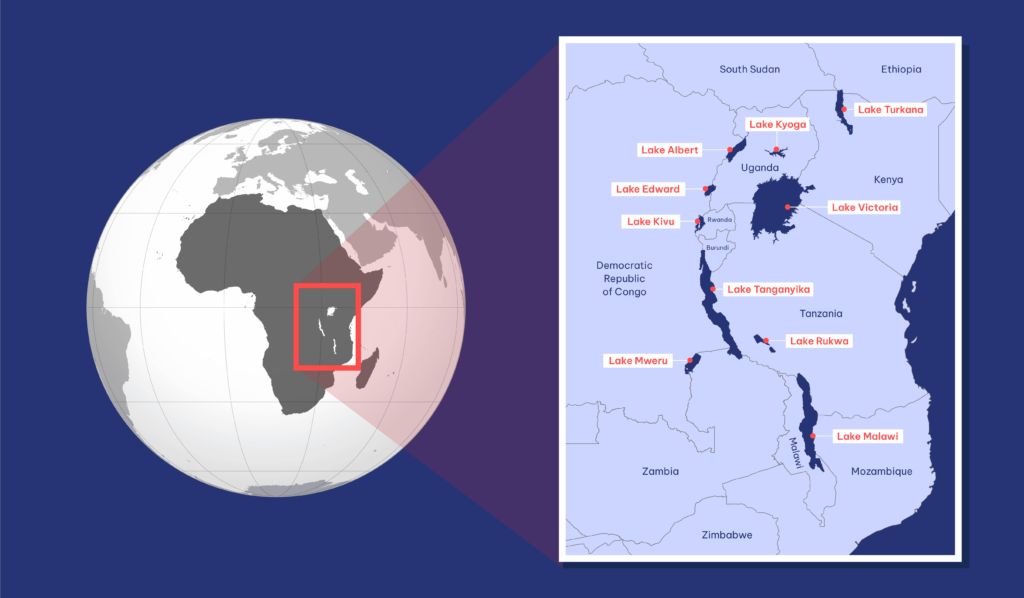

The Great Lakes region that encompasses Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo is among Africa’s most beautiful regions. Cloud-covered volcanos, terraced fields, lush jungles, and lakes dot the landscape. It is also among the most violent.

The June 2025 peace agreement signed at the White House between two of the region’s countries (Rwanda and Congo) is positive but follow-up, especially with Burundi, will be necessary.

Background on the Great Lakes Region

Following the 1994 anti-Tutsi genocide in Rwanda, the Rwandan Patriotic Front led by Paul Kagame drove the Hutu génocidiares across the border into the Democratic Republic of Congo, forced the Hutus’ French advisors to decamp for Paris and began Rwanda’s transformation into the Singapore of Africa.

But the Hutu extremists found fertile ground in UN refugee camps across the border in Congo. Burundi, too, allowed in Hutu insurgents intent on renewing the genocide. The UN not only did not disarm the Hutu terrorists, but allowed them to take over education in their camps, perpetuating their extremist ideology across generations.

Beyond Rwanda, more than six million people have died in successive Congo wars over the past three decades. The UN refugee camps along Rwanda’s borders became epicenters for instability. The UN peacekeepers in Congo rival only the employees of the UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA, which administers Palestinian refugee camps) in corruption and involvement in violence. The UN’s Congo personnel, for example, often work in tandem with génocidiares and Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda (FDLR) terrorists to stage cross border attacks into Rwanda. The Great Lakes region shows that the United Nation’s venality with the Palestinians is the rule, not the exception.

Rwanda and Burundi are similar in size to the US state of Maryland, and both were Belgian colonies. Hutus, Tutsis, and a small population of Twa (pygmies) populate both countries, as well as the eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of Congo. After the anti-Tutsi genocide in Rwanda, the discrepancy between the two countries grew sharply. Kagame embraced self-sufficiency in Rwanda; he curtailed corruption, avoided debt traps, and grew local industry. The World Bank believes Rwanda could become a middle-income country by 2035 and a high-income country by 2050. Burundi, meanwhile, is the second poorest country in Africa and the world after South Sudan. The average Burundian makes just over $40 per month.

Meanwhile, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, President Félix Tshisekedi’s first term was coming to a close in early 2024, with a record of self-enrichment and nepotism, and no infrastructure improvements to justify re-election. He responded with incitement against not only Rwanda but also his own country’s centuries-old ethnic Tutsi community. He declared Tutsis were aliens and interlopers, and encouraged attacks. Terrorist groups proliferated. While European diplomats accepted Tshisekedi’s denial of responsibility, this never passed the smell test. How could Tshisekedi suppress militants in southern Congo (where Chinese mining companies operated) but not do the same in eastern Congo?

President Trump Intervenes; What Should Come Next

In his first term, President Donald Trump was engaged behind-the-scenes to bring calm to the Great Lakes region. Ambassador J. Peter Pham, his special envoy to the region, cajoled Democratic Republic of Congo President Félix Tshisekedi and Burundian President Pierre Nkurunziza to cease allowing Hutu insurgents to utilize Burundi’s territory to strike at Rwanda. For a time, both Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo constrained Hutu terrorists on their territories.

In the first months of his second term, on June 27, Trump hosted the foreign ministers of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo at the White House. “Today, the violence and destruction comes to an end, and the entire region begins a new chapter of hope and opportunity, harmony, prosperity and peace,” Trump declared at an Oval Office meeting. The Rwandan and Congolese ministers then signed a peace agreement in a ceremony presided over by Secretary of State Marco Rubio.

Trump’s peace efforts were a life raft for Kinshasa’s failing kleptocrat. He got to save face, though the promise of megadeals over minerals and rare earths will go nowhere if Tshisekedi continues to loot his country and treats commercial law with disdain.

The real missing piece is lowly Burundi. On January 11, 2024, Burundi shut its land border with Rwanda, cutting itself off from trade and leaving its citizens impoverished. Its president Évariste Ndayishimiye rules his country as a fusion of Saddam Hussein and Marie Antoinette. Freedom House ranks Burundi only marginally freer than Russia. Meanwhile, when Burundians complain about food shortages, Ndayishimiye responds by telling them he has avocado trees on his palace grounds and, if they lack food, they should plant some themselves. Burundian journalists I interviewed describe a society spiraling out of control where sycophancy reigns supreme and criticism means years in prison.

What lights the fuse in Burundi is the fact that Ndayishimiye no longer trusts his own army. In 2023, he sent 10,000 Burundian troops to eastern Congo. In theory, they were peacekeepers; in practice they prayed upon local villagers. Just as Cubans do with their international doctors corps, Ndayishimiye appears to have pocketed the peacekeepers’ salaries. In February 2025, M23 forced their withdrawal, leaving dissatisfied, angry armed men extorting their own increasingly hungry people at home.

The Burundian dictator now has three choices. First, he can deploy the army against his own people. This buys time, but the military cannot loot empty pantries. Second, he can again send Burundian troops abroad. Some remain in Somalia, South Sudan, and the Central African Republic, but they are ill-disciplined and ineffective. In an era of decreasing budgets, the UN cannot afford yet another scandal involving peacekeepers abusing locals. Third, Ndayishimiye can seek asylum abroad. Just as Congo’s Tshisekedi spent his exile years in Belgium delivering pizzas, so too might Ndayishimiye head to Belgium to allow competent management to raise Burundians out of their morass.

Peace in the Great Lakes of Africa will never last if Burundi remains a haven for militants and terrorists.

Trump deserves praise for seeking to extinguish a wildfire that consumed millions of lives when it last burned out of control. But by ignoring Burundi, the missing piece, he essentially walks away with the conflagration only 90 percent contained and a wind storm on the horizon.