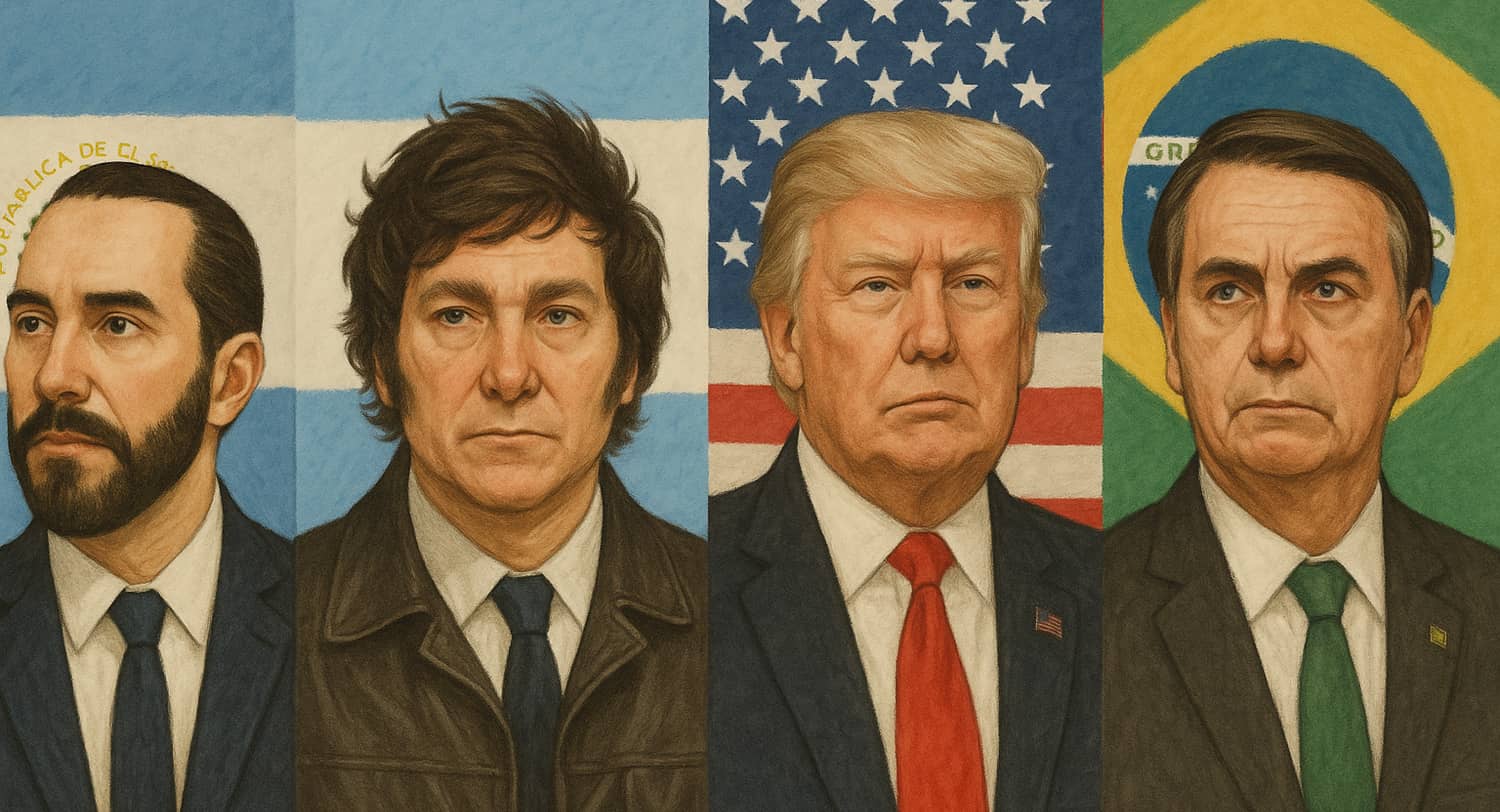

Three leading right-wing politicians in Latin America, Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele, Argentine President Javier Milei, and former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, have made much of their relationships with President Trump.

Bukele’s Prisons at Trump’s Disposal

Of the three, Bukele has established the closest rapport with Trump, a major shift from the suspicion with which he was viewed by the Biden administration.

Bukele was elected as El Salvador’s president in 2019, pledging to end the country’s intolerable levels of violence. His solution was the massive militarization of law enforcement and the creation of a huge “anti-terrorist” prison in which tens of thousands of persons have been held without any semblance of due process. he sent troops into El Salvador’s Congress, intimidating it into passing his budget, and forced the replacement of the attorney general and five Supreme Court judges, while harassing critical journalists.

The Biden administration sharply criticized El Salvador’s democratic slippage and imposed sanctions on several of Bukele’s associates for corruption. But Bukele remains popular in El Salvador, where the public is prepared to accept the trade-off of a vastly improved security situation for loss of civil liberties.

Trump, while out of office, was initially critical, and in a 2024 speech he asserted that Bukele was “sending all his criminals, his drug dealers, his people that are in jails, he’s sending them all to the United States.” Bukele got the message. After Trump, now back in office, ramped up removals of illegal immigrants, Bukele agreed to accept flights of deportees and place them in his massive prison. Bukele has also received third country nationals from the United States, including Venezuelans accused of being in the “Tren de Aragua” criminal organization.

Unlike Biden, Trump has made no effort to push back on his authoritarian practices as shown by the recent detention of human rights activist Ruth López which prompted only pro forma expressions of concern from the Department of State. Bukele is the only Latin American leader to have been formally received at the White House since Trump’s return, where Trump praised him, stating: “You are helping us and we appreciate it.” Donald Trump, Jr. attended Bukele’s second inaugural.

Bukele remains very much in favor in Trump’s Washington, and Donald Trump, Jr. attended Bukele’s second inaugural. But there are reports that Bukele has made deals which allow gangs to continue criminal activity such as participation in international narcotics trafficking in exchange for their acquiescence in his mass incarceration of street level criminals.

Milei Joins the War on “Woke”

Javier Milei’s libertarian ideology initially made him a marginal figure in Argentine politics. However, increasing frustration with economic decay led Argentines to give him a chance at power. Since taking office in early 2024, his tough spending cuts have brought Argentina success in taming inflation, but Argentines feel the pain of his austerity program;

Milei, like Bukele, has sought to cultivate Trump, based on a shared “outsider” profile. They met at a CPAC (Conservative Political Action Conference) event in February of 2024 and again in November of 2024 at Mar-a-Lago, where Milei termed Trump’s return to office as “the greatest political comeback in history” and in turn was praised as “a MAGA person” by Trump. He attended Trump’s second inaugural in Washington and maintains links with figures in Trump’s orbit such as Steve Bannon, who has said “we love him,” and Elon Musk, to whom Milei gave a chainsaw—the symbol of his campaign to shrink the state—at the 2025 CPAC event.

Trump’s and Milei’s economic views are in many ways quite different. As a libertarian Milei is a believer in free trade, while Trump detests it. Milei has urged creation of a US-Argentina free trade agreement to no avail and has not even been able to get negotiations underway to limit the impact of Trump’s current tariffs.

But Milei has aligned himself with Trump in other areas. Milei views himself as a leader of the global right, along with Italy’s Giorgia Meloni and Hungary’s Viktor Orban. He followed the United States in withdrawing from the World Health Organization and has raised the possibility of withdrawing from the Paris climate change accord. At the United Nations he joined with the United States in opposing a resolution calling for Russian withdrawal from Ukraine. And he has become ever more strident in denunciations of anything smacking of “woke” positions in areas such as abortion and “gender ideology.”

Under Trump, the United States has been helpful to Argentina in one area, its negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). When the latest deal providing Argentina with $20 billion in fresh funding was concluded, the Argentine press was quick to attribute success to the Milei-Trump relationship. Unquestionably, the latest loan could not have gone forward without US support.

However, Milei has been relentless in economic reform efforts, unlike his feckless predecessors, and thus the country has credibility with the IMF quite independent of US ties. He did benefit from a key gesture from the Trump administration, with the visit of Treasury Secretary Bessent, which helped calm markets at a time when the Fund’s latest loan had yet to materialize. But it is worth noting that despite some ideological distance, the Biden administration also was generally helpful to Argentina under Milei.

Bolsonaro Needs Help

Former army captain Jair Bolsonaro, whose 2019-22 term as Brazil’s President overlapped with Trump’s first term, now faces criminal charges over his alleged involvement in coup plotting after his failed re-election bid. When in power, he had forged a close relationship with Trump and relished being known as “the Trump of the tropics.”

He was received at the White House, where he spoke of a shared commitment to “traditional family lifestyles (and) respect to God our creator against the gender ideology or the politically correct attitudes.” There was also some genuine, if modest, substance to the Trump-Bolsonaro relationship: an agreement which liberalized two-way agricultural trade, access for the United States to Brazil’s space launch facility, and the largely symbolic designation of Brazil as a “Major Non-NATO Ally.”

Relations cooled under the Biden administration, which disliked Bolsonaro’s authoritarian tendencies and his hostility toward environmental measures and indigenous rights. He ran for re-election in 2022, but faced a strong opponent in former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva together with a soft post-COVID economy. As the election drew near, there was fear in Washington that Bolsonaro, who had openly admired past Brazil’s military governments, would not respect an adverse outcome. Defense Secretary Austin and CIA Director Burns used visits to Brazil to underscore the military’s need to respect the democratic process.

After Lula’s victory, protests broke out, culminating in the seizure of key government buildings in Brasilia by a mob hostile to Lula. Evidence surfaced that some senior officers had been involved—with Bolsonaro’s connivance or at least awareness—in plotting a military takeover. Since then, these officers, together with Bolsonaro himself, have been subjected to criminal proceedings aggressively pursued by Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes. If convicted, Bolsonaro could face ineligibility to run for president in the next election in 2026 and even a prison sentence.

Bolsonaro’s son Eduardo has gone to the United States to seek American support for an amnesty for all involved in the alleged coup plotting, and Brazil’s Congress is debating such an amnesty, though it has not prospered so far.

There are reports that the US is considering imposing sanctions on Justice de Moraes under the Magnitsky Act (affecting banks where he maintains accounts) and visa restrictions. This has come as he has imposed fines on Elon Musk’s X platform and on Rumble, a platform especially favored in far right circles. But while the Trump administration may be able to make de Moraes’ life more difficult, it seems unlikely that such steps would derail the case against Bolsonaro.

The Limits of Friendship

Other Latin American conservative leaders would like links with Trump. Ecuador’s Daniel Noboa, like Bukele, campaigned on a promise to deal with surging violence, and then put troops on the street and made mass arrests. When he ran for re-election in 2025, he met with Trump at Mar-a-Lago shortly ahead of the runoff vote. He has offered to allow the US to base counternarcotics surveillance aircraft in Ecuador, as was done until it was banned in 2009. But Noboa has also made clear his unwillingness to follow Bukele in accepting deportees from third countries.

As for Panama’s José Raúl Mulino, Trump’s threats to retake control of the Panama Canal have left him in damage control mode. He has defused tensions by not renewing the contracts of Chinese firms to operate port facilities, but the relationship is likely to remained strained, especially as the Trump administration has reportedly cancelled the visas of former Panamanian presidents and other prominent figures.

The relationship between Trump and the populist right in Latin America is a mix of ideology and national interests on both sides (and self interest in the case of Bolsonaro). Trump and those in his circle seem attracted to the idea of a global movement against traditional center-left establishment politics. Latin America is a region like Eastern Europe where this has gotten some traction.

Trump’s agenda prominently includes clamping down on illegal immigration from Latin America. Of the three leaders, relations with Bukele seem strongest since he is the one most willing to help on this American priority. As long as El Salvador’s prisons are available for deportees from the United States, Bukele is likely to enjoy a privileged place in Washington.